“What’s the point of another architecture biennial?”

Many of us heard this remark at opening parties, waiting in line for a free spritz. And while it may be a fair question, it is a fair question only the first time. If the last 15 years recorded the proliferation of biennials there must be a reason – and asking, “What’s the point?” a second time means that you just didn’t do your homework.

I studied biennials and triennials for years. I learned how they attract people and investments, how they exhibit, how they differ and compete. I learned how they cheat, sometimes. After two years of delays, 2022 marked the reopening of many events. I am about to embark on a European tour to visit 6 biennials in 8 weeks. A Biennalista. This is my diary.

Chapter 1 – Tallinn

2 September 2022

Covid gave me way too much time with myself. Too much reflection, too much introspection. Some people locked themselves into a room and had a great time, but I’ve crawled out of the pandemic feeling like I haven’t really learned anything new.

Screens didn’t work for me; pixels don’t allow the information to sediment into knowledge. I need to be there, to read the room, to absorb discussions. The banter with the speakers, a beer after.

I wanna get back into the game, but the streak of *iennials (biennials and triennials) opening in the next weeks kinda scares me: Do I still have the energy to engage in all that?

I will never have the answer, I can only dive head-first. I’ll take it as a stress-test.

I reach for VOLUME 54 On Biennials, the issue I edited in 2019. There was a diagram showing the intersections of 11 international events; that’s a good start to plan my European ping-pong.

The Tallinn Architecture Biennial should be the first one; Oslo and Timișoara open the same weekend – I pick Romania, I was an advisor there. Rotterdam is low-hanging fruit, Tbilisi maybe a long shot; Lisbon intrigues me, never been, so their conference will be the wrap-up.

6 September 2022

I’ve been in touch with the Tallinn biennial press office for a few days, after receiving a press release that felt as warm as a personal invitation: Jesus Christ, automated marketing tools are getting too good. It takes me a few emails to understand that their press budget is already gone – so no travel expenses, but they still have a hotel room available. Better than nothing, I ponder, I’d go anyway for this topic!

The complex relations between food and architecture are the focus of Edible – Or, The Architecture of Metabolism, the 6th Tallinn Architecture Biennial. The theme had already caught my attention before the pandemic, when the two curators were announced, for personal reasons. Fresh off my Master’s (in architecture), my career took a sharp detour: in 2017 I co-founded a FoodTech start-up with another friend, later incubated in the Copenhagen School of Entrepreneurship. Our angle was food waste; for years we had been involved in local initiatives – I can proudly name the two times I left food on my plate – and we saw the opportunity to scale up/speed up our efforts through the use of artificial intelligence.

When I saw architects stepping into food-related challenges, their responses never really satisfied me; I still remember graduation projects that, after months of research, came up with pink-lit skyscrapers to grow lettuce in the middle of London: “It can provide food to 900 people…” No, my dear, maybe it can provide a fucking lettuce to 900 in a city of 9 million – and in the most expensive plot on the globe! AAAAAARGH!

Sorry, but the thought still gets my blood boiling. Breath…you are going to Tallinn… they will have real solutions there, an inner voice reassures me.

I have very short notice to get organized, the opening night is 2 days away. The only flight compatible with my shallow pockets leaves after the vernissage, but I still can attend the 2-day symposium with most of the selected participants.

That’s alright, the inner voice tells me, and I know arriving late wouldn’t let me break rule #1 of biennials: don’t judge an exhibition by the opening. The race between content and free drinks permits only one result – I learned it much to my cost in 2012, after building the Canadian Pavilion in Venice.

8 September 2022

I hop on the plane while Schiphol airport is still waking up, but the free-coffee machines work around the clock (yes, there are!). The trip I booked forces me to stop in Helsinki, and while I sip the third cappuccino of the day I realize that I’m sitting 88 km away from my final destination. I am not a flight-shamer, but I do feel guilty. There is water in the middle, ok – but for an 88 km flight you don’t need a plane, a catapult is enough. But my sky-high hopes trump every sign of guilt: I gotta go because I’m sure Tallinn has solved food systems!

As the wheels touch the ground I’m already on my way to the symposium, hyped like a door-to-door salesman on cocaine; I register, throw my trolley somewhere dark and bow down, palms to the ceiling, ready to receive the long-awaited answers.

But I missed the intro sermon, I don’t know the liturgy, and my attention is exceptionally volatile. For the first few minutes, words reach my ears but don’t make it up to the brain, like wild salmons on their day off. Maybe my expectations are too high, or maybe I’m overdosing on caffeine.

To retrieve some sort of cool I try to focus on the venue – it is impressive, how come I didn’t notice it. We are surrounded by a metallic maze of pipes, stairs, and suspended passages, two hidden blue-and-orange spotlights create a wonderfully mysterious atmosphere. I can’t say if it is planned, but when looking up a soft mist torn by the two ultralight beams appears, like the depths of a forest; this is some concert-type of scenography – and so I wait, expecting Kanye to pop up from the heavy machinery.

But no Kanye shows up on stage, my euphoria finally fades, and I manage to take my first look at the program. Despite my long-lasting interest in the topic I have never heard some of the names. It must be because curators Lydia Kallipoliti and Areti Markopoulou operate in different geozones: Markopoulou is the Director of IAAC in Barcelona (Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia), an interesting talent-pool when it comes to applying new technologies, and Kallipoliti in based on the East Coast of the United States, where she made a name for herself teaching at the most prestigious architecture universities.

The different milieus of the curators emerge interestingly throughout the selection of speakers: together with academics from Europe and the US, there is a strong representation of innovative business ventures, a mix that I have hardly ever seen in an event with architecture in the title. When catching the presentation of Allison Dring (CEO of Made of Air, a carbon-capturing company), I immediately think, She is not an architect – and I mean because she is spot on. No beating around the bush. No useless details, no convoluted periphrasis or hunger for neologisms. People from the start-up world know how to pitch an idea; they know how to pick words that make you fantasize – and rest assured, their company is turning your fantasy into reality, right now.

My years in incubators whisper that I should be suspicious of these tactics, but I want to believe that the biennial has done its due diligence and these are all credible projects – so I lean back and let myself be nurtured by their hopes and dreams (and companies). And it is rather uplifting.

Let’s face it: many of the urban challenges of our time have been picked up by people that have never studied the dynamics of a city – but this should only push architects and planners to venture more into the world of innovation, not just sitting outside and sulking. Mitchell Joachim, architect and founder of Terreform ONE, is a good example of this courageous attitude: on stage he showcases a great ability to appeal alternatingly to the general public, to business investors, or to an architectural audience.

Incommunicability.

But as this term hits my mind, the architecture world has a great chance for immediate redemption. “For thousands of years mankind used clay as a building material…” say Columbia professors Lola Ben Alon and Sharon Yavo Ayalon, and I listen distractedly, “…but not many of you know that in Haiti they use clay to make cookies…”

Wait, WHAT?

“…although they have no nutritional value…”

I want clay cookies, where are the cookies.

“…for centuries people ate baked clay…”

WHERE ARE MY COOKIES. Tension.

“…so with our students we made edible clay cookies…”

I – WANT – MY – COOKIES – RIGHT – NOW. The climax of a gangster movie.

“…we tried different consistencies, textures…”

BITCH BETTER HAVE MY COOKIES, like Rihanna sang (kinda).

“…we studied the practice of geophagia…”

Talking, talking, talking for 10 interminable minutes – and still, no cookies.

I mean, your lecture has one of the most memorable beginnings, and you blow it by over-explaining it? You see, that’s what I mean: if you had a start-up, you’d have handed us cookies already, 100%. Locked and loaded baby! Bam: millions from VCs, raining like it’s the UK. You goddamn architects, when will you learn the power of anecdotes!

The day proceeds without cookies, nor any particular highlights. The biennial has organized a dinner for the press, and the walk to get to the restaurant gives me the opportunity to see how much Tallinn has changed since 2017. That was the year I had taken a road trip through the three Baltic republics, to realize that, culturally, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia have far less in common than I expected; their landscape and size are comparable, and so is the aversion to Moscow – in particular in Estonia and Lithuania; less in Latvia where 25% of the population is ethnically Russian – but that’s about it.

So, since the collapse of the Soviet Union the three countries separately embarked on ‘nation-building’ missions: each one has restructured its national identity, rediscovering (or sometimes creating) their foundational myths, and designing what they want to be remembered for.

Estonia decided to present itself as a young democracy that embraces technological innovation for both governance and private business, and in doing so gained worldwide recognition with the nickname e-Estonia. The repositioning of the country has attracted global attention and foreign investments, and Tallinn is the symbol of this success: a cashless city that spent a lot in micromobility, infused with a special creative energy with cranes dotting the skyline.

Another interesting element of this nation-branding campaign is pushing Estonia toward the Nordic sphere of influence (by Nordic we mean Scandinavia+Finland). In Tallinn you encounter countless Nordic references, in signs, billboards and even menus, all claiming, “Look at us, we are with Finland now, not with the others”. This shift is highly strategic: indeed to break free from the imprecise idea of ‘Baltic’ – but especially to gravitate toward a part of the world identified by economic stability, efficient services, and good design. Industrial areas beside the old center are undergoing redevelopment, with residences, offices, and public spaces winking at the style of its northern cousins.

I have the feeling that architects really do design here; they don’t have to reinvent themselves as graphic designers or writers (sigh).

9 September 2022

The following day opens with a strange realization: I am almost the only press correspondent left at the symposium – all the others have either gone on an organized bus-tour, or are strolling around in the sun. These things always get me mad: what are you gonna write about the biennial if you missed half of the projects’ explanations?

…and then the media complain about the lack of trust.

Anyway, the first day has offered me no cookies but some interesting insights, so I decide that I won’t go to the biennial exhibition today, I’ll focus on the presentations. Despite the well-parked fleet of e-scooters outside, time would be too tight. Better tomorrow.

From the people on stage it seems that the Fab-Lab ethos is having a resurgence – it was promising back in the 2010s but I lost track of it. Many of the projects have been developed within the context of IAAC, but as much as I’m intrigued by the application of technological advancements, these often leave me with a bitter aftertaste: the food aspect seems to be stitched on, a posteriori. Like, do you really need to 3D-print facade panels to put strawberries into them?

They look like solutions looking for a problem. Like that pink skyscr… oh no not again! Breath. I simply think that [inhale] the team maybe has focused more on the technical details rather than on the concept [exhale].

‘Fab-Lab tinkering’ is one of the two macro-trends that I am starting to notice. The second tends instead to understand food in strictly metaphorical terms – the metabolic exchanges of a city, the inflows and outflows – but with limited relevance to food per se, including the final keynote of Beatriz Colomina, always fascinating but slightly off-topic. Some speakers fall into the trap of organic food nostalgia, the pastoral myth of ‘the way things used to be’, but interestingly, their projects do not always follow the same conservative trajectory. Are they saying these things to please the crowd? That’s never a good sign: food is becoming ideology.

Then, two guys take the floor: there is something off in their posture, cloaked in oversized sweaters, like they don’t fully belong. When they say their research has been prepared by mixing three ingredients – artificiality, desire, and alienation – I know I am looking at two Strelka alumni. Sharp, witty, caustic, they go by the name Black Almanac. One of them pulls out a script that sounds as thick as molasses and as pungent as Roquefort, a dense concentrate of high references, etymologies, and punchlines that they must have learned from their mentor Benjamin H. Bratton during the year in Moscow. Reading from the podium through his small, rounded glasses, the speaker calls out what he dubs “agrarian simulations”, the invention of traditions, promoting an accelerationist attitude to embrace the ever-present technologic alienation of our food systems, in the name of transformation.

Ten minutes of well-choreographed speech, and you don’t know what hit you (if you tried to follow). I make a mental note to talk to them at the end – I fear that their position won’t reap them any particular success with this audience (and I am right).

Rather than their provocations, it is the depth of their reflections that struck me, the ability to hover over disciplines and weave seamless threads between fields; fields until then unrelated and unrelatable.

I’m a sucker for this type of research. I will admit that it is not for everybody, and it often risks making some people feel dumb (including other speakers), but if this is the result, so be it.

It’s still September, but I have food for thought for the entire winter.

10 September 2022

I wake up early to visit the Estonian Museum of Architecture, finally ready to experience what people have been describing to me for the last two days.

Exhibition designer Sofia Krimizi has subdivided the space using colored strings that connect the floor to the ceiling. The effect vaguely reminds me of the web-like spaces of Chiharu Shiota, but here the density of the threads does not try to gain a spatial presence.

I always found it fascinating to see an exhibited project after I’ve heard of its genesis: some carry a surprising strength in the translation from story to artefact (like the rice sculptures of Mitchell Joachim), while others make you thankful to have listened to the explanation.

An enigmatic conglomerate of levigated stones sits at the center, the work of Andrés Jaque/Office for Political Innovation, who unfortunately were not at the symposium. I heard that their piece really came alive during the vernissage, an artistic performance that now makes me regret my late flight.

I am still alone – I was the first ticket of the day – but the space is not quiet at all: silence is broken by an impressive kinetic installation by Caroline O’Donnell (Ecological Action Lab, Cornell University), in which a complex mechanism of weights and drops, suspended in mid-air, spills water rhythmically into a pool below.

Many of the participants decided to exhibit their research samples: some laid out on a table, some in petri dishes, some arranged vertically. The most convincing effort to compile a complete taxonomy is the installation of Ben Alon and Yavo Ayalon, who displayed their studies on clay in a long plexiglass matrix, from building material to edible clay.

That’s where I finally find them – the objects of my desire for the past 48 hours, the great joke that never got to the punchline, my Estonian coitus interruptus: an array of clay cookies, 4 lines of 15, neatly arranged by color!

This section is not protected by plexiglass, the display is open: is this an invitation? I look around, still no one, so I snatch two baked cookies, one brick-red and one chalky-white, and I run outside on the grass, my heart pounding like when I first stole candies from a supermarket.

I can’t believe I am holding them in my hands: little discs of 4-5 cm in diameter, their look is the telltale of a previous liquid phase, with a little pointy tips like when the spoon leaves the meringue. They look more appetizing than I thought.

Before I can wonder wtf, I take a bite of the red clay one.

Crack.

Flavor doesn’t exist, but the chew is exactly how you would expect it: sandy bits grind through your molars, making a squeaky sound that reverberates straight into the brain. Jesus Christ they gotta be damn poor in Haiti, is the only thought I hear through the noise.

I give the white cookie a try. It must indeed be chalk, it crumbles better than the red one, but the resulting dust coats the tongue with an impenetrable film, a waterproof layer that kills the purpose of salivating.

As I said, I take pride in remembering the two times I left food unfinished.

I mean, three times.

[A few weeks later – more or less when I finally digested the infamous Haitian delicatessen – I have a long call with Triin Ojari, the Director of the Estonian Museum of Architecture. When our paths crossed, I was always left with the impression of a very competent and witty professional, so when she asked me what I thought of the biennial I was very happy to give her my honest opinion.

The number of visitors was satisfactory, she said, the media reception had been positive, but the local architecture scene had expressed some discontent with the development of the topic – too academic, too abstract, too… flibbertigibbet. Was this something to keep in mind, to steer the following edition toward pragmatism?

My opinion was completely different: first of all, you should never evaluate the performance of a topical biennial at the end of the exhibition. A topical biennial has the ambition to produce a body of knowledge about one specific point – food, in this case – and that’s why it is legitimate to put its international reputation ahead of its local reception. A topical biennial isn’t just a display of works. It aims at driving the debate, and to do so it prioritizes depth over concentration. A better indicator would be how many catalogues have been sold worldwide, or how many times they have been picked up in university libraries over 10 years.

A good topical biennial reverberates through time.

Moreover, since the architecture market in Tallinn is florid, the biennial – a publicly funded event, with the support of the Ministry of Culture among many other institutions – should not follow the money but rather lead the discussion on a cultural level, to compensate for the systemic push toward construction. Given the circumstances, the Tallinn Architecture Biennial didn’t only have the liberty, but I would almost say the obligation to rebalance the scale; it shouldn’t just please its potential target audience, but challenge it to stay sharp.

I saw that Triin took notes.

I mean, a different angle is exactly what you’d expect from a Biennalista.]

Chapter 2 – Timișoara

22 September 2022

I know the curators of BETA 2022 (the Timișoara Architecture Biennial) very well: Davide Tommaso Ferrando and Daniel Tudor Munteanu are the masterminds behind the Unfolding Pavilion, the parasite exhibition that has so often stolen the show at the last 4 openings of the Venice Biennale.

Their pirate attitude resurfaced in Timișoara, where they have been planning an incredibly ambitious event titled Another Breach in the Wall, exploring how to exploit loopholes in public space. In the year-long preliminary research they have collected a very large number of projects that occupy the a-legal interstice between legality and illegality, examples from all eras and latitudes – like when architecture provocateur Santiago Cirugeda realized that parking a construction skip was free by law, so he filled one with concrete and planted a swing for kids to play.

The case studies have been gathered in an incredibly comprehensive catalog, set to become the main resource for whoever will show interest in the topic. Moreover, in some cases, the curators even agreed with the authors to replicate their interventions in selected locations of Timișoara – including Cirugeda’s swing-in-a-skip.

All, of course, on top of the main exhibition.

The production must have been gargantuan I get to thinking the day before flying to the opening [and little did I know, the young team led by Alexandra Trofin will really surprise me in the coming days].

23 September 2022

Despite never setting foot here before, Romania feels oddly familiar: the Latin root makes language not impossible to decode, and the place vaguely reminds me of snapshots of a region that I learned to know fairly well, ex-Yugoslavia. Perhaps it is because Timișoara is located at the west corner of the country, one hour north of the Serbian border, and maps don’t reveal any topographic obstacle indicating separate geographies, no river, no mountain. But where do the Balkans end? I wouldn’t exactly know, and for once not even Google is able to give me a straight answer. Trivial, but the question keeps lingering in my head.

I have been invited to Timișoara because I was a jury member to evaluate the temporary installation for Traian Square, right beside the BETA exhibition. Compared to other journeys, jury duty has been smooth sailing; not too many projects to evaluate, clear schedule, no tempestuous egos taking over discussions. We selected a rather unconventional proposal, because we saw in it the potential to involve audiences that would never go to an architecture event: in a nutshell, Traian Square will turn into a pop-up football field – real grass and all, with a couple of light structures beside. The concept made us travel back to when we were kids, turning backpacks into posts – but we also loved how the authors (Zenaida Florea, Cristian Bădescu, Bogdan Isopescu, and Pia Onci) designed the inefficiencies: no perimeter fence meant that the ball would go out-of-bounds and constantly involve the passers-by.

The night of the opening of BETA, it is clear that the installation is a success: from 150 meters away, a human wall of coats and jackets blocks my sight. It is impossible to see what’s going on, but the synchronous movement of heads suggests that there is a ball involved.

[I recently heard that the installation was so successful that it was replicated again the following year, for Timișoara European Capital of Culture 2023. BETA was also involved in one of the most debated installations, called Pepiniera: a scaffolding tower of 27m in the square where the Revolution sparked in 1989, slowly covered by 1306 plants growing throughout the 12 months of the ECC23].

The atmosphere at the opening is joyful and relaxed, also thanks to Free Beer. Unlike any other gratuitous beer that you can get at a vernissage, Free Beer is indeed a beer (produced by a nearby brewery) but also part of Another Breach in the Wall (the Danish collective Superflex meant Free as in Open Source). And when even the beer is part of the experience, I start understanding BETA’s ambition: not only a topical biennial, but a temporary world-building effort.

24 September 2022

The program for the next two days includes a tour with the curators, two panels, presentations, and discussions. Everything revolves around the Monkey House, the Secession building that hosts the main exhibition, beside the square where people are still playing football.

Another Breach in the Wall is a sequence of delightful moments of subversion. For a person like me, a kidult who hasn’t given up on the idea that fun could still be part of your daily routine, this tongue-in-cheek approach is both entertaining and insightful. Whether the goal was activism, provocation or anything in between, Aaaah that’s clever is the thought that most often pops up.

Exploring the labyrinthine spaces of the Monkey House I find a gem: in one of the subterranean rooms Theo Deutinger is displaying his new visual research of country dividers – every single ditch, fence, or wall constructed or reinforced between 2017 and 2022 with the purpose of separating nations. It is the extension of his Handbook of Tyranny, an incredible book of data visualizations portraying the daily cruelties of twenty-first century dictatorships.

25 September 2022

Sunday morning, and curiously I have nothing planned.

During the opening night I overheard an interesting story: 6 nights before, four volunteers got together and packed their backpacks with plastic bottles full of yellow paint. They pierced a hole through the cap, so that a thin drip would mark their path, and went to follow four separate itineraries, all carefully planned to connect the 20+ installations that BETA had scattered in the city. The line itself was part of the exhibition: it replicated the work of MOMO, a graffiti writer who in 2006 used this technique to tag his name along 13 km of downtown Manhattan.

The result was one continuous yellow line, 23 km long, running across every neighborhood of Timișoara – and almost immediately people took on TikTok and Instagram to wonder about that yellow trace on their doorstep.

The story is intriguing, and since I have the morning for myself I decide to put on my running shoes, check the closest point, and start following the trace.

Three hours, and I return to my hotel mind-blown.

You wouldn’t notice the yellow mark until you noticed it – and then you would see it everywhere. It was mysterious, captivating. Following it would indeed occasionally lead you to encounter unexpected interventions; some were quirky, some paradoxical, some playful, some ironic – but all tied by a yellow-and-pink palette and a small sign.

And even along the stretches in which you wouldn’t find any installation (or maybe I missed it) the treasure hunt would reward you with a free tour of Timișoara, from churches to playgrounds, from the university campus to railway yards, through gardens and quiet blocks.

In my run I even saw how people were appropriating the yellow trace: along a couple of blocks, patches of wet soap revealed how owners tried to scrub away their private 8 meters, with little success. Some others tried to cover the yellow drip with sand – only to thicken it.

Incredible. Such a simple gesture solved the biggest problem of a biennial, the relation to its context: how does a biennial relate to its hosting city? This is particularly true for topical biennials because this typology prioritizes depth into a single topic at the expense of the local scene (see Tallinn).

I’ve always thought that the mission of any biennial is not to focus on its belly button and try to provide architectural experiences to people that would never intentionally go. And now, these 23 km… Why not reach out to local running clubs and organize the Timișoara Half Marathon around it? The municipality…Jesus Christ, think about the possibilities!

It’s not the fatigue (I’m well-trained), but my legs are literally shaking.

The story meanwhile is blowing up: local newspapers have written about it (without yet knowing the authors), it is all over social media, and you witness in real time the contractions and birth of ‘baby conspiracies’ (and that’s when you know you have the upper hand).

When I come back to the Monkey House people are almost freaked out that I followed the whole path. For many, I understand that the yellow line was not a great intuition to capitalize upon (in terms of attention, like someone in advertising would do), so that’s why they really did not expect the spotlight and attention it is attracting.

It had the potential to transform wondering into wandering.

Many strategies like this one could be used by *iennials to break the disciplinary boundaries, if only people from other fields – merchants of attention – would be involved in the months before. They could take care of planning the PR scenarios, orchestrating the media reactions, and nudge the public attention in the right direction towards these intuitions.

It is not by chance that both revolutions and coups d’état start by seizing information – every effective world-building effort involves a media takeover.

26 September 2022

Never would I think that simple yellow line would keep me up at night, but it struck a personal nerve.

When I was appointed Curator of the Sarajevo architecture festival Dani Arhitekture 2020, we had been plotting several of these intuitions to attract attention, experimental campaigns completely unheard of in the world of architecture – but then the global pandemic killed our plans. Six months of work went to waste (and being up so late reveals that I have not yet recovered), but that thin drip of paint told me we were 100% on the right path.

You shouldn’t judge based on outcome but on process – that’s what I tell myself as I try to get some sleep. A long day is ahead of me.

A couple of days earlier I had to plan a way (the cheapest way) to visit the Triennale in Oslo. First, find someone to host me – don’t wanna trade a bed for a kidney – then, flight.

My proximity to Serbia compels me to fly from Belgrade, and since the person hosting me in Norway is an old friend from Bosnia (we worked together during my curatorship in Sarajevo) I thought to show her my gratitude with an original krompiruša – the Balkan potato pie that can turn even the most easy-going person into a hard-to-please. People demand quality when it comes to it.

Despite my initial resistance, the staff of BETA insists on booking me a car and driver to Serbia, so now I have a post-it with a name and a meeting spot right across the block. A black Mercedes with fume windows pulls up. Marko is a man of few words, and I happily abide by his conditions.

After just 10 minutes on the highway, the black car takes a swift turn and enters a suburban residential area. The detour finds its explanation when a 60-year old woman hops on board; I will share the ride to Belgrade with her. Seeing how nonchalantly my travel companions take to the informal carpooling makes me giggle, because I finally got the answer to my question: Yes, Balkans.

My stop in Belgrade is surgical: in-and-out of the pekara (bakery), through luggage control with the most delicious potato pie – so much grease that I’m surprised they didn’t stop it for liquids.

My flight lands in Oslo at night, and the krompiruša turns out to be a great gift for my Bosnian host, and a perfect midnight snack before another *iennial.

Chapter 3 – Oslo

27 September 2022

Buildings, roads, people, movements: everything in Norway looks silky, dipped in a dimmed light that conceals the passing of time: 9am? Possible. 9pm, equally possible. It reminds me of the long days spent on set, when I worked in advertising… the sky is off-white, like when you inadvertently turn off the sky layer in Photoshop.

Then the rhythmic vibrations in my right pocket interrupt further digressions.

[+995, Georgia.]

“Hey man, problems with the Domus correspondent, we have two spots for press, one still open. Send me your passport details”.

Every time I met the 3 founders of the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial, Oto Nemsadze struck me as the calm one. His telegraphic language speaks urgency.

“On it. By the way, who’s the other one?”

“Nick. You know him right?”

I kinda do. Nick Axel had my position at VOLUME before I joined; his career later brought him to lead e-flux architecture and the architecture program at the Rietveld Academy, but the fact that I didn’t hear a lot about him in the editors’ room gave me the impression of a tumultuous departure. Despite living in the same city for years, we never really met, but when Oto mentions his name I realize that I expect him to be a competent architecture critic, and a difficult person to work with. Anyway, he’s going to be a useful travel companion. When Russia invaded Ukraine last February, I heard he was collaborating with the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center in Kyiv, so he must be familiar with the geopolitical intricacies of the Caucasus.

But the metallic squeak of wheels in a traffic-less city reminds me this is not the Caucasus: this is Norway, where public transport costs way too much and measures delays in seconds. I wonder if the two things are related.

Since my last visit in 2016, the main venue of the Oslo Triennale has moved to the edge of the center. It left Doga and Sverre Fehn’s glazed room in the National Museum to relocate into the old Munch Museum. By default I walked to the wrong location, so now the tram is taking me through the Barcode, the waterfront neighborhood that I left behind six years ago littered with cranes and piles of materials. The ride shows me that the construction boom is now expanding along the coast, where the desire for a private view is at peak monetization. “Building developers have a lot of negotiating power when they talk to regulators here”, is the complaint of my Bosnian host, an architect herself.

The tram drops me on a hill, where a low modernist building stands out at the edge of a short driveway.

The theme chosen by the Triennale Curator Christian Pagh is Mission Neighbourhood, “a laboratory for the creation of more diverse, more generous, more sustainable neighborhoods.” The very ‘open to interpretation’ topic already marks a sharp departure from the previous edition, which instead decided to shrink its focus on degrowth.

The exhibition space is articulated in a sinuous sequence of rooms, each exploring an aspect of neighborhoods; a simple layout, spacious and organized, but nothing really stands out. The selection of projects seems moderately nice, but definitely not groundbreaking nor inspirational. The insights that you can get are quite banal, and it has a very Scandinavian focus in contrast with the apparently universal theme.

I wander haphazardly around images and maquettes, looking for a solution that I didn’t expect – something to hold onto, anything, please. But before I realize, I’m already at the end of the exhibition; the circular layout makes visitors walk very fast. I remember that the 2016 Triennale left me with a lot of food for thought, my hopes for 2022 were equally high, but… frankly… I am a bit disappointed.

On my way out I notice a big panel beside the exit door. Who the hell put the curatorial statement at the end?

Damn. I have entered from the back, what an idiot. Finally something to blame on not selling tickets. I look nonchalantly at the panel but I’m slightly embarrassed about my rookie mistake. The thought vanishes as I start reading: the text is different from usual intros; it doesn’t state big ambitions with even bigger words. Everything is sooo acceeessible. Just time to ask myself where all the neologisms went, and then the most unexpected thing ever actually happens.

I laugh.

Did I just laugh? More shame.

Don’t blush, you idiot. Sad, I said. You don’t laugh at exhibitions. *iennials are not for laughing! Are they? Wait, why aren’t they?

I can’t remember exactly what, maybe the witty formulation of an old concept, but yes I laughed – and this is when I start to understand: I may be in Norway, but this is a Danish exhibition. I feel a tingling excitement running through my body, like when you are close to solving an enigma that bugged you. Yes, it all makes sense: the curator, the mission, the exhibition space, the tone of voice!

I spent years in Denmark for my Master’s, swinging between unexpected culture-shock and fascination for their communication skills (they even managed to make us eat musks, for God’s sake – see New Nordic food). So, let me explain, starting with the chief Curator Christian Pagh.

Pagh is quintessentially Danish: optimist attitude, hair perfectly messy, casually wearing sneakers and dark-everything, like the people that put a lot of effort to look easygoing. Unconventional choice, many thought when he was appointed. His jaunty presence shares little with the academic sadness of most curators – because there’s nothing to share. To the Oslo curatorship Christian arrived from the other side of the barricade, the world of advertising, leading an agency that became notorious for placemaking and city-branding campaigns.

Like many of today’s global Danes – the Bjarkes, the Jan Gehls, the Colville-Andersens – Pagh’s work navigates complex concepts using the language of the masses. The result is a no-bullshit approach that embraces the ethos of the optimistic entrepreneur, and rejects any intellectualism. You can recognize it already in the title of the Triennale: Mission Neighbourhood… it doesn’t fuck around; its ambition is strictly operative. And what do you need to do before you operate? You quantify! “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it,” as neoliberal guru Peter Drucker famously said, and that’s why Christian steered the Triennale’s catalog into becoming a tool for evaluation, called Neighbourhood Index. Christian, you bloody trader of attention, now you officially got mine: I am intrigued.

I suddenly remember that it’s not the first time Oslo has set itself to reinvent the idea of the catalog: in 2019 the group of curators (Maria Smith, Phineas Harper, Matthew Dalziel and Cecilia Sachs Olsen) decided to jump into the world of fiction, with novels, poems and stories painting what a degrowth-world might look like. They seemed to proclaim, “Who needs case studies? We need world-making!”, and the result was the interesting book Gross Ideas: Tales of Tomorrow’s Architecture, a companion rather than an exhibition catalog.

All these thoughts happen in a second, or what feels like a second. I don’t know how long I’ve been standing obtusely in front of this introduction.

Looking back at the exhibition that I’ve just sprinted through, only now do I notice the abundance of models and renderings, rather than floorplans – in classic Danish fashion. As I learned in Aarhus, technical drawings might be incomprehensible for the average Joe. And have you ever seen a detailed section coming out of Bjarke’s office? Exactly.

My disappointment starts fading: maybe I simply wasn’t the target audience for this exhibition. Moreover, why should I, an architect, be the target of an architecture exhibition? I honestly do not have an answer. Because Bjarke’s diagrams don’t talk to architects, they speak to your mom and dad. And the tone of voice of that panel sounded so… fresh. Too fresh for architects; real architects don’t laugh in public.

I get a flash of the construction sites that I have seen from the tram; it is the missing piece of a puzzle that I didn’t think I could like. Today Oslo doesn’t need inspirational buildings, nor academic digressions. The scale and speed of the coastal developments shows that Oslo must guarantee itself a certain level of design quality, functionally and spatially.

I finally understand my initial dismay: the Triennale has courageously decided to not speak to the local architects – the usual visitors – in order to instead engage with the opposing fringes of its potential audience: citizens and building developers. It has presented itself as the institutional facilitator between the ambitions of the business world and the necessities of the public.

And to do so, Oslo had to move to Denmark.

2 October 2022

In hindsight, the position of the 2022 Oslo Triennale was hard for me to chart: too local for a topical biennial, too specific for a general biennial. The more I thought about it, the more it looked like an unexpected mutation of a catalyst biennial.

Catalyst biennials are the rarest typology: they aim to directly intervene in the city, to modify the way it functions for a timeframe that extends well beyond the duration of the event. They are often extremely ambitious – and difficult to push through: curators and participants must turn their commitment into a civic role, and not use the city as a backdrop for their own performance.

They usually start as bottom-up events where you cement the involvement of a pre-existing community, to leave them the keys of the transformation for the years to come.

But in Oslo the push doesn’t look like it’s coming from below – and this is particularly fascinating for me. A top-down version of a catalyst: Once again, Scandinavia leaves me culture-shocked.

Chapter 4 – Rotterdam

12 October 2022

One week ago I was invited to Ljubljana to participate in the annual conference of LINA, a European network connecting promising architects with architectural institutions (including many of the biennials and triennials that I have reviewed throughout the years). The notice was so short that no flight was affordable (it had to be a 21-hour Flixbus ride), but for the return I found a plane landing at Rotterdam Airport (I didn’t even know it had one). In a nutshell, that’s how I decided to stop by and visit IABR, the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam.

A few years ago I researched the event for VOLUME, and I was very critical: some indicators told me that the potential of IABR was particularly high (percentage of architects in the population, etc.) yet the management seemed slack. Especially its media presence, which was laughable. So, when at the end of 2021 I saw the appointment of Saskia Van Stein as the new Director I got hopeful again – a very charismatic character, not scared of questioning even the most established routines. When I talked to her the following March, she warned me that the transformation would require time, so the 2022 IABR would have been part of a transition. Don’t worry Saskia, I will show up by chance, and with low expectations.

The exhibition IT’S ABOUT TIME (curated by Derk Loorbach, Véronique Patteeuw, Léa-Catherine Szacka, and Peter Veenstra) wants to draw a line 50 years after the publication of The Limits to Growth by the Club of Rome – and from the get-go I’m already dubious about the theme: what more can we add on the topic of global warming? I mean, the usual audience of biennials already seems well-versed on the topic…

It takes a short walk to get to the western harbor area, I’ve never been to this part of town. Suddenly, yellow flags announce that you are approaching the venue, a circular building of 70-80 meters in diameter majestically standing out from its surroundings – a former natural gas container I guess. Walking into such an industrial mastodon has something archaeological to it, with its huge hall and exposed radial beams. I gotta say, +1 for the location, impressive.

The exhibition is not cluttered, and visitors are naturally attracted into a central axis defined by 2.5 meter-tall panels, wrapped in a patterned silver fabric that dialogues beautifully with the metal carpentry of the roof. The sequence of these ‘outerspace’ panels follows the timeline of global warming: reports, essays, but also works of fiction, like movies and music, are catalogued neatly to make the topic digestible. The most difficult thing must have been to select just a few relevant items, but the story that these archival evidences tell is linear and rather enjoyable.

It makes me reflect: the strongest aspect of this display is actually to make order and arrange them in the visitor’s mind, because it’s true that we all have heard a million times about the challenges of climate change, but hardly ever in a didascalic way – with a title, an author, and a date for each reference. What I expected to be a risk, here, became an advantage.

Coming to the end of the timeline, the space opens up into three sections summarized by enigmatic terms: Accelerator, Activist, and Ancestor. The three names sound intriguing, and another textual panel has the curatorial explanation: they represent three attitudes that the curators identified during the phase of research, three attitudes that designers usually show when dealing with global warming.

Accelerators make use of smart technologies to achieve efficiency. Activists work together with local communities on small-scale bottom-up projects. Ancestors have the ability to slow down the hype cycles, and develop long-term perspectives.

The projects on display in each section are good projects – some even outstanding, like the installation on lab-grown cultured meat by 2050+ – but it is the curators’ taxonomic effort that really stuck in my mind.

I have to say, today I still find their tripartite framework absolutely appropriate to organize the myriad of projects that state an environmental ambition. Once you have categorized them, you can see if they fall short, and by how much.

If the goal of an exhibition is to provide visitors with the tools to interpret reality, this has been the main strength of this edition of IABR.

Chapter 5 – Tbilisi

14 October 2022

I have just a day to rest – 24 hours to do the laundry and jump on a plane to Georgia. I’ve been hyped to go to Tbilisi since Oslo, when I received Oto’s invitation: Rotterdam was good, but I learned that the most interesting biennials happen at the periphery of the discourse. Plus, rarely have I seen a group of founders so complementary like the 3 people behind the Tbilisi Architecture Biennial. The few years I spent in the start-up world taught me that you need different profiles and attitudes, but the wrong mix can result in catastrophic failures.

The passion of Tinatin, Gigi and Oto, with their differences and competences, is one reason for the upward trajectory of the TAB.

Tinatin, Tiko for everyone in Tbilisi, is the activist of the 3 founders: although her studies brought her out of Georgia, first to Spain and later to Berlin, she remained involved in her motherland’s fight for social justice. I had the chance to meet her right after her interview for the VOLUME issue On Biennials, and since then our paths have crossed in Tbilisi and in Venice, where TAB curated the 2023 Georgian Pavilion. Every time I was stunned by her dedication, a strength that drives her to the brink of exhaustion before every opening, but that doesn’t seem to scratch her monolithic belief in what she does.

The third founder of TAB is Gigi Shukakidze, a different character. He pursued the architectural profession and even got nominated for the Mies van der Rohe Award in 2022, but what always struck me was his profound knowledge of hip-hop: I thought, he must have been the early-internet type of kid, when illegal downloading would make you discover countercultures that were inconceivable for your context. Compared to Tiko or Oto he talks less often about years abroad – perhaps because he didn’t have any, or maybe because he found his way out of Georgia through other forms of culture, like black music.

These are just speculations, but his sense of humor makes me think that our lives have run parallel for decades.

I first met them altogether in 2019: I had researched biennials for years, leading a unit of 5 people that was scrutinizing the performance of 11 international events, so I was incredibly happy when the TAB invited me to Tbilisi to present the results of that inquiry. But as much as I knew about the peculiarities of each biennial – the venues, the visitors, the sponsors – I didn’t expect that TAB had broken the only rule of biennials: the previous event did not happen 2 years before, but 30.

I discovered that the last Tbilisi Architecture Biennial was in November 1988, the first and only architectural biennial to be held in the Soviet Union. The week-long event featured works from the USA, France, Switzerland, and the rest of the USSR, and had a jury made up of notable international architects. It reflected Tbilisi’s role as ‘an island’ of relative artistic freedom within the authoritarian state, and its receptiveness to new ideas within a closed society.

The collapse of the Soviet Union, and the accompanying political instability, meant that the event ceased to continue. The 2018 Tbilisi Architecture Biennial was the first to take place since Georgia regained its independence in 1991 – and it was Tiko, Oto, and Gigi that revived it. The format had shape-shifted every edition: 2018 took place and intervened on the Gldani neighborhood (catalyst biennial); 2020 was a digital edition and explored the Commons (topical biennial). The 2022 theme is Temporality, and it seems to be organized as a festival, with a public symposium, several events, and public visits to 4 funded installations. Interestingly, there is no curator.

Nick Axel and I will arrive from the Netherlands on the same plane, after a quick stop at Sabiha Gökçen Airport in Istanbul.

The terminal is surreal. We are surrounded by shaved heads, with red patches and white headbands. I hadn’t seen a white headband since Allen Iverson retired from the NBA, but this has nothing to do with basketball. We are at the epicenter of the global hair transplant industry: this hall welcomes so many sad hairlines that you might call it Sabiha Gökçen Hairport.

From my very first chat with Nick, I cannot understand where my suspicion about him came from: he is an incredibly kind person, with a good sense of humor. This gap makes me think of a neuroscience article I recently read about first impressions: they form at the intersection between our pre-existing expectations and sensory data, whether the two match or not. During the three seconds that this comparison takes place our thought does not have a shape yet. After these few seconds, we form an opinion and snap back into autopilot.

And talking about sensorial stimuli, Tbilisi Airport sends you straight into overload. We are greeted by a gigantic billboard reminding us of the 8000 past vintages they had in Georgia – a subtle hint to the local pride, wine making. Even passport control is in on it: the officer distractedly looks through the stamped pages, before handing me a 250 ml bottle of Tsinandali red with my document.

Amazing, nation-branding sneaked into bureaucracy!

The arrival gate is packed. Waves of visitors crash onto hundreds of men lingering on the threshold of the building: official cabs, riding apps, normal drivers, everyone is negotiating a cheap lift into town. The hard surface of polished granite tiles and blue glass reverberates a constant, indistinguishable background noise. Nothing out of the ordinary you might think, but it is almost 3am. For some strange reason most of the flights land here at night.

Me and Nick are staying at Fabrika, a gigantic soviet sewing factory recently flipped into an urban attractor: hundreds of rooms, spaces for creatives, bars, graffiti all over. Although this Richard Florida formula has been tried over and over, I remember thinking in 2019 that here the result felt more genuine – maybe because the motivational quotes on the walls sounded less cheesy than at WeWork, or maybe because eavesdropping on the conversations I noticed that the occupants were local. In any case, I’m happy to be back.

The days ahead of us feel exciting and demanding. With a schedule full of events scattered around, the morphology of the city (along a river, with the center at a bottleneck that then flows out into the mikrorayons) tells me that we will be ping-ponged a lot between opposite ends, so I better get some sleep in.

15 October 2022

The early sun hitting my pillow leaves me with no doubt, I am not in the Netherlands anymore. The sunrays paint the space with a light yellow tone and every object is accompanied by a dark doppelganger; I cannot help but think how oddly familiar this feels for an Italian, 3600 km away. After all, vines don’t lie – generally, latitudes where you could make wine also produced comparable lifestyles.

Despite the few hours of sleep, when I go downstairs I meet a very energized Nick: we are about to go to the opening of the public installation Protected Lands, conceived by the Ukrainian architecture collective ФОРМА [Forma], and he has worked with them during his months in Kyiv. He tells me that, to participate in person, the men must have received the approval to travel abroad from the Ukrainian government itself; they could receive the call to arms anytime.

The short ride to the location reveals how central the topic of the invasion must be in every conversation. Blue & Yellow flags, “Ruzzki go home” slogans, and signs in support of Ukraine are dotting every corner of the capital. It doesn’t surprise me, Georgians have been there before: on the 8th of August 2008 Russia launched a military operation into the Georgian territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, and the war continued until French President Sarkozy negotiated a ceasefire. That invasion also had a symbolic meaning: the date of the Russian attack was chosen in clear disrespect of the Olympic truce, the millenary tradition of suspending conflicts during the Olympic Games (the opening ceremony was that same day in Beijing).

That’s why the invasion of February 2022 evoked a complex set of emotions for Georgians: sympathy for Ukrainians and fear that Russia might soon turn its gaze back to the Caucasus. If Russia won in Ukraine, Georgians had reason to fear that the Kremlin would be emboldened to come and finish the job it began 14 years before. If it lost, they were also aware that their small country could be an easy consolation prize.

On top of the conflicting emotions, Tbilisi was suffering the very tangible consequences of the displacements. A report estimated that 110,000 Russian emigrants had settled in Georgia by October ‘22, mainly the capital, a city of 1.2 million people. “Universities are recording a massive drop in enrollments. Freshmen coming from outside have not found any affordable rooms. They will not study this year”, a TAB volunteer told me.

The taxi drops us in a grey, monumental square, an oversized void delimited by an eclectic Sports Palace, a casino, and a Subway sandwich shop.

We are immediately welcomed by Tinatin and Oto, followed by a tinier version of Oto, his kid. The space is buzzing with cars and pedestrians, but the people involved in the TAB are very recognizable: we are the only motionless beings in the frantic space. We are all standing on the sidewalk, beside a gargantuan structure… wait, what is a war checkpoint doing in the middle of Tbilisi?

The 5×5 meter concrete-and-dirt colossus seems to have emerged from the bowels of the square – volumetrically alien yet chromatically fitting. It was built stacking prefabricated slabs onto each other to create walls, apertures and a roof, and covered by soil that still contains some organic matter.

ФОРМА’s project is a provocation about instant fortifications proliferating in Ukraine: how long will they need them? What will become of them once the conflict ends?

The final effect is spectacularly eerie, but some people carelessly pass by it.

Not everyone though: the pavilion especially attracts people of an older age. Even more interestingly, I notice that their experience is almost always the same, like dancers following a rehearsed choreography: they walk to the structure, circumnavigate it inquisitively (counterclockwise), and eventually stop in front of the same small portion of concrete wall. A short description is hanging there, displayed in three alphabets – Georgian, Cyrillic and Latin (in English) – and the sandy dirt on the ground forces them to lean over to read it. Each one reads it carefully, top to bottom… and then they look around, bewildered – first on their right, then on their left, then again on their right toward us, chatting just a few meters away.

It is at this point that some of them come closer to us, looking for an explanation: “Why are you doing this? Do you want Russia to attack us?” some ask the Ukrainian authors, who are understandably too tired to engage in lengthy confrontations after, you know, escaping a war just the day before.

“They are provocateurs; leave them alone”, Tinatin tells me. “Old people are brainwashed by TV propaganda.”

I do see her point, the result of years of polarization, but what I just witnessed – the almost perfect curation of an architectural experience to reflect on the present – is making my head spin: I have never seen young architects engaging so profoundly with old people. Old people are never our target audience. We don’t know how to talk to them, so we don’t talk to them at all.

My mind digs up memories from 20 years ago, in my graffiti days. When I was getting busy with a wall, it wasn’t parents or teenagers who would come to me. Surprisingly, the most curious about my work were old folks.

Parents had “no time for this nonsense”; kids would observe, but from afar. Old people would instead come and genuinely try to understand what I was doing, the reasons, the meaning; not all of their assumptions were correct – esoterism was their evergreen – but with a bit of time, our discussions would quickly move to art forms, techniques, and styles. I even managed to convince one of them to spray-paint with me – the most gangsta granny alive.

I cherish those memories very dearly.

In that monumental square I had noticed that same seed of curiosity. But why wasn’t it blossoming?

I think again about the neuroscience article I read a few days before: while opinions start forming in milliseconds, it is believed that we have a longer timeframe to decide where we stand on them – like two directions of the same vector, positive or negative. In these initial three seconds, an opinion has not yet crystallized, so it is possible to nudge it in different directions; but if you don’t pay attention the cognitive process will happen instinctively – which for the majority of people means that they will overcome these instantaneous uncertainties with the help of preformatted frameworks, such as experiences, hearsays and stereotypes.

I can’t stop thinking about the estrangement after they finished reading the text. Looking around, slightly dazed. “[one] But…[two] what is this thing doing here? [three]” their eyes seem to wonder. Perhaps something as simple as: “Exactly, that’s what the Ukrainian people are wondering too,” could have built empathy.

I keep repeating to myself: The conditions were ripe, everything was in place, but we underestimated the last three fundamental seconds of the experience.

I would want to discuss my hypothesis – with the authors, with Tinatin and Oto, with the old people themselves – but the serene look in the eyes of the Ukrainians, 200 days after the invasion, overwhelms me with a sudden shame like an instant fog. Who am I to suggest ways to bridge conflicts? What do I know about war? Who the fuck am I?

I move a few steps aside and silently observe some more. Similar experience, same estrangement, some occasional confrontation. Maybe, I ponder, maybe only an outside observer can capture some clues, personal involvement trumps all nuances.

My three-second intuition seems more and more valid – it is just not the right time to discuss it.

Profoundly moved by the whirlwind of thoughts, I lose track of the time I’m spending looking at this odd dance of seniors; the second installation is about to open soon on a hill just outside of Tbilisi, we must hurry up.

As our car climbs up the steep twisty road, I notice the disorderly forest of recent towers sprouting throughout the center, symptom of the unequivocal influence that real estate developers have on the city.

Italo-Georgian architecture studio Noia talks about this power asymmetry with its intervention on Mshrali Lake, one of the many lakes dotting the capital’s surroundings. Mshrali Lake is seasonal; it appears in winter and dries out during spring (mshrali means dry in Georgian), and the park where it is located has recently attracted private interests for an urban expansion. The architects decided to plant 121 burnt wooden poles into the lakebed, following an orthogonal grid that oddly resembles the pillars of an underground parking garage. In a few weeks water will appear, and these elements will stand out there, enigmatic, between a measuring tool and a dark prophecy.

The whole experience has something religious to it: the precision of the grid in the flowy landscape might recall theories of cosmos’ Grand Design; the charcoal finishing of the wood has a Franciscan minimalism.

Even the walk to reach the lake resembles a procession – our clothes, predominantly black and navy blue, could easily be mistaken for uniforms. I wonder what the park visitors must have thought when they saw 100 people deviating – altogether – to go up on a slope and disappear into the woods. A sect? Collective suicide? Eternal salvation? Another take on Temporality, I guess.

16 October 2022

The second day is dedicated to a symposium in Kartli, an old sanatorium a few kilometers outside of the city, on the banks of the Tbilisi water reservoir.

The tragic history of the venue is back in the public eye after the invasion of Ukraine: originally born out of the Soviet ‘right to rest’, following the dissolution of the USSR, the sanatorium was temporarily used to house families escaping the 1992/93 conflict in Abkhazia. For these IDP (Internally Displaced Persons) the adverb ‘temporarily’ stretched 30 years. Three decades, cramped collectively in a structure conceived for individual stays of a handful of days at a time (and in warm seasons).

Remember the balconies of Aalto’s sanatoria from our architectural history courses? Ok, now replace “the intuitions of the Finnish master” with “the intuitions of a Soviet bureaucrat” and you may grasp the spatial quality of Kartli: no services, cave-like ceilings, cheap materials that soon led to dilapidation.

The state of perennial precarity made some people lose hope: in January 2022 one resident tragically took his own life as an act of protest. During the past 30 years, the 150 families residing there have been promised relocation over and over, but in the meantime they have learned to adjust: they colonized the useless apertures, built kitchens and bathrooms, shared spaces, organized with spokespersons. One of them, Irma Nachkebia, has been invited to join a panel: educated as a nurse in Abkhazia, she has lived most of her life in Kartli.

Irma sits comfortably at the barycenter of the hall, an environment she clearly knows well. Her physical presence and deep calm voice suggest a natural authority that in other circumstances might be called charisma. After listening to the experiences of the other panelists, she reveals details about the everyday life of the families she represents, often lingering on the beauty of living together through the hard times. Her marked sense of humor may surprise some people, but is not new to me – it is the same sense of humor my friends in Sarajevo share, a way to reclaim the narrative that paints them only as tragic figures, heroes bound to fail. Laughter is the way to reaffirm their humanity, their normality in an abnormal situation.

The hall where the symposium is taking place is detached from the main building; the high ceiling denotes a different function, but it is hard to understand what it originally was. Inside, a trailer is the most visible amongst a myriad of working tools stored there. We are not alone: one kid circles furiously on a small pedal-less bike, intent on going underneath the trailer at the highest speed possible; other kids play football against a wall.

Long horizontal windows let in plenty of the damped October light, but already now the single glazing doesn’t do much to protect from the sharp draughts.

Jesus, why here? It’s cold!

As I entered, the first impression kicked in automatically, and after a moment I felt profoundly ashamed of it.

Yes it is cold, I tell myself. 30 years cold.

Once again the first thought spilled unfiltered, but yesterday’s lesson taught me how to neutralize it until it’s malleable: catch it within the first three seconds.

The mix of cold and shame makes me more attentive to the symposium: the presentation of two small figures makes them suddenly stand out like giants. Their names are Anna and Tania Pashynska, and beyond being ‘twins’ it would be difficult for me to describe them with a single word: designers, artists, curators, urban activists.

I knew them as the co-founders of MetaLab, a Ukrainian urban laboratory I discovered during my first trip to Tbilisi, but I had lost track of them since then. They live in West-Ukraine in the region of Ivano-Frankivsk, and since the beginning of the invasion they have risen up to the challenge to house as many internally displaced people as possible, using any space that they manage to refurbish – be it an unused or abandoned building or a newly built one. Under the name Co-Haty (love in Ukrainian) they used their multiplicity to their advantage, managing to speak to every possible ally on the way to their mission. They convinced international organizations to fund their goal, local craftsmen to cooperate, suppliers to contribute with materials, and politicians to gain credibility and support – all while providing dignified homes for thousands of Ukrainians fleeing the frontline.

I have to admit, my first sensation is not awe but disgust – in myself. They may be my age but they are changing the world. They seem full of vitality and hope, even if in a few days they are expected to go back to the conflict. The comparison is sickening, and I try to shut it down as quickly as I can. To let off steam I look at the kids still playing football; one is wearing the Azzurri t-shirt of the local sensation Khvicha Kvaratskhelia, a star in Naples.

No need for an identity crisis right now.

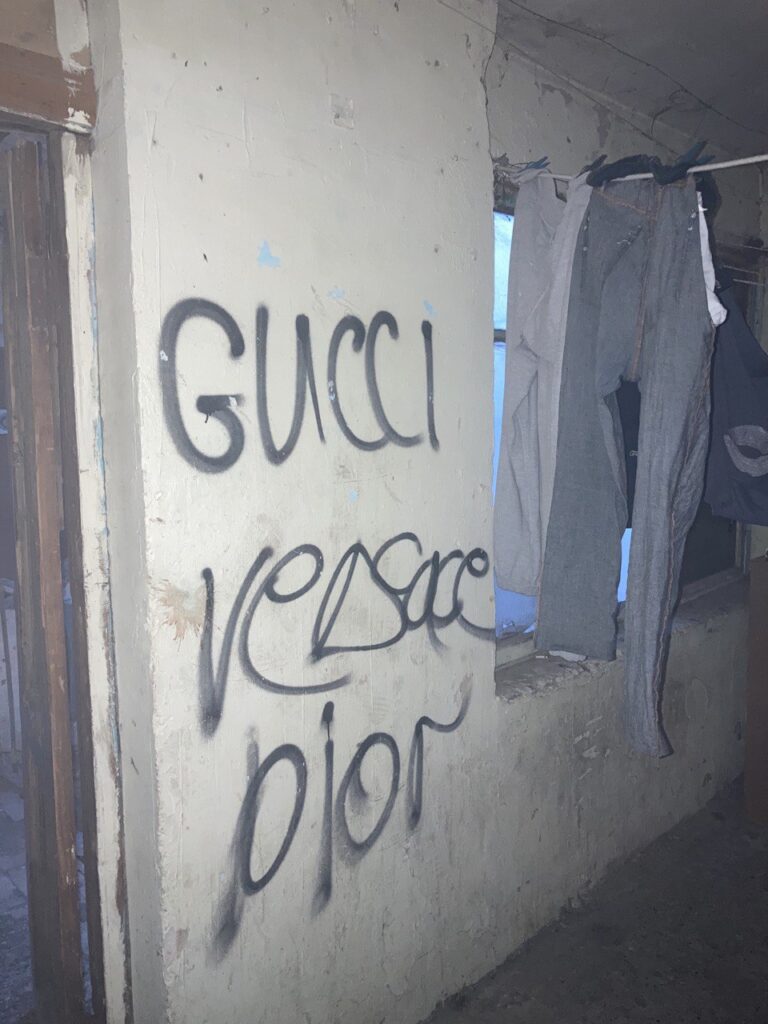

The speech of Anna and Tania wraps up the symposium, and we are all invited inside to visit some of the apartments (for lack of a better definition). A forest of hanging clothes adorning the stairs already feels like we are in a part of the private spaces. On the walls, spray-painted Latin letters add to the surrealism: Dior, Versace, Gucci.

Virgil Abloh would have loved this.

Every floor has a different smell. On the second floor, someone must really like spices; on the third floor, there is smoke but no-one seems to pay attention. We enter some of the homes further up, and each one is a surprise. Looking past the crumbling concrete and the shaky cables, you immediately recognize the vivid individuality of the inhabitants: pink wallpaper over-imposed with religious effigies; movable curtains to secure levels of privacy; big kitchens, or no kitchens – some neighbors realized it was better to share and save space.

A few people dodge us nervously, rushing down to the third floor; the smoke has thickened. Someone says they should call the fire department, but it all seems to get back under control a few moments later. A real emergency or an everyday occurrence? None of us can really tell, but the air is still tense. Tania looks at her sister and breaks down in tears: “We plan homes for 2 years, 5 years…” she sobs, moved by the visit, “but what if it takes more? We must do more, Anna!”

Goosebumps take over my forearms, and I respectfully lower my head.

17 October 2022

My days in Tbilisi are running hectically, overstimulated by all the inputs that my brain is trying to retain.

Every street sign catches my attention: in my idle moments, I set myself to decode the exotic characters of the Georgian alphabet, a sequence of round twirls that vaguely resembles the Laos alphabet (and shares absolutely nothing with it).

The dinners altogether, every discussion with Nick and the volunteers, every transfer from one corner to another: I can’t say exactly what is part of the TAB and what is not, but I approach everything (even the breaks) with an enthusiasm that I wouldn’t expect. This thing is energizing, this thing is so not a biennial!

You must have noticed by now that I usually categorize biennials into three (general, topical, and catalyst), but TAB escapes all my definitions. The organizers put together a city festival rather than a biennial, so the mechanisms of curations are completely different. That’s why they didn’t need a curator.

21 October 2022

I’ve been thinking about Tbilisi for a few days now.

I have the feeling that such an event almost needs the constant transfers from one place to another: these moments are the buffers to elaborate what you have just seen, to let impressions sediment into clarity. At the same time, each movement grounds your experience in the city and enriches it with contextual knowledge. The sensorial experience of a pavilion, or the words of a symposium, stay alive for much longer than the time allocated in the program.

It is fascinating that TAB focused on Temporality because I could only describe this edition as the dialogue between two very different temporal scales: the month and the instant. The month was the ever-present low-voltage, stretching throughout every single moment of the program – including all the moments not in the program. It gave context. The instant, on the contrary, was high intensity, the sequence of the many three-second insights. It gave depth.

Using a biological analogy, the petri dish of the month allowed the instant to reach critical mass, and crystallize into deep reflections.

The ability to switch gears from one to another has characterized four days that I will not forget easily.

“Do we need another biennial”, people wondered at the beginning of my tour.

Maybe not. Maybe we need more city festivals.